To order Hitler Sites ($55) click here

Hitler and cronies' annual re-enactment of Beerhall Putsch march,

November 1938:

Launch Real Player

This option requires Real Player.

Click

here to download Real Player

Launch

Windows Media Player

This option requires Microsoft's Windows Media Player.

Click

here to download Windows Media Player

During the November 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler tried but

failed to take control of the conservative Bavarian state government and the

Weimar government in Berlin. He was already head of the National Socialist

German Workers’ Party, with 70,000 members the most powerful political party in

Bavaria. He and many other Germans viewed the freely elected government of the

Weimar Republic as an abomination that the victorious Allies had imposed after

the German defeat in World War I. Moreover, Germany was in the throes of

catastrophic hyperinflation, and French troops had just occupied the Ruhr.

Hitler wrongly believed that the social upheaval these two calamities were

causing would assure success for the putschists.

During the November 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler tried but

failed to take control of the conservative Bavarian state government and the

Weimar government in Berlin. He was already head of the National Socialist

German Workers’ Party, with 70,000 members the most powerful political party in

Bavaria. He and many other Germans viewed the freely elected government of the

Weimar Republic as an abomination that the victorious Allies had imposed after

the German defeat in World War I. Moreover, Germany was in the throes of

catastrophic hyperinflation, and French troops had just occupied the Ruhr.

Hitler wrongly believed that the social upheaval these two calamities were

causing would assure success for the putschists.

The Bavarian government’s leaders were scornful of the Berlin government, and

were themselves plotting the formation of a new nationalist dictatorship in

Berlin. Three men controlled the government of Bavaria: Otto von Lossow, head of

the Bavarian army; Gustav Ritter von Kahr, General State Commissar; and Hans

Ritter von Seisser, the Bavarian police chief. These men sympathized with many

of Hitler’s views but did not like some of his radical ideas.

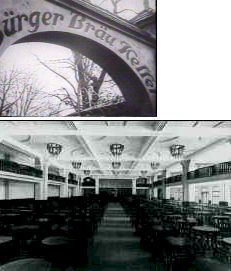

On the evening of November 8, 1923, the Putsch began at the Bürgerbräukeller,

where a large group of prominent Bavarians had gathered, among them Kahr,

Lossow, and Seisser, as well as Hitler and Erich Ludendorff. The former army

general quartermaster, Ludendorff was the man who was mainly responsible for

Germany's military policy and strategy in the latter years of World War I.

On the evening of November 8, 1923, the Putsch began at the Bürgerbräukeller,

where a large group of prominent Bavarians had gathered, among them Kahr,

Lossow, and Seisser, as well as Hitler and Erich Ludendorff. The former army

general quartermaster, Ludendorff was the man who was mainly responsible for

Germany's military policy and strategy in the latter years of World War I.

For half an hour, Kahr had been reading a prepared speech to the crowd of 3,000

packed into the Burgerbräukeller, when Hitler made his grand entrance. A clutch

of men in steel helmets, Hitler’s storm troopers, appeared, and pushed in a

heavy machine gun. Hitler materialized, accompanied by two armed bodyguards

brandishing pistols. Hitler stood on a chair, and, drowned out by the tumult, he

pulled out his Browning automatic pistol and fired a shot through the ceiling.

Hitler announced that the revolution had broken out and six hundred armed men

surrounded the hall. The Bavarian government was deposed, he shouted, and he

would form a provisional Reich government. He requested Kahr, Lossow, and

Seisser to follow him into an adjoining room. Reluctantly they complied.

Pandemonium reigned, but Hermann Göring, a former World War I flying ace and

Hitler’s ally, urged everyone to be calm. “You’ve got your beer,” he said

(Kershaw, 1998).

Waving his pistol in the next room, Hitler shouted that no one would leave

without his permission. He proclaimed the formation of a new government, himself

at the head. Ludendorff, Lossow, Seisser, and Kahr all agreed to be important

members. If things did not work out, Hitler declared that he had bullets in his

pistol for his collaborators and himself.

Things definitely did not work out. Lossow, Seisser, and Kahr, tepid

revolutionaries from the outset, left the hall and proceeded to inform state

authorities that they repudiated the putsch.

Meanwhile, Ernst Röhm led another group of Hitler loyalists in the

Löwenbräukeller across town. Röhm managed to capture the Bavarian War Ministry

but bungled by not taking over the telephone switchboard. Lossow was thus able

to bring loyalist forces to Munich from nearby towns. Army troops and state

police were soon besieging Röhm and his followers.

The next morning, a bitterly cold one, with the putsch rapidly crumbling, Hitler

and Ludendorff decided on a demonstration march to Röhm’s rescue through the

city. Hitler believed that a march would engender overwhelming support.

Ludendorff thought that the army would never fire at him, a revered military

leader, and that if he were in the front ranks, the soldiers would back down.

The march began at noon. A cordon of men carrying banners preceded Hitler,

Ludendorff, Göring, and Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter, another party leader.

At the Ludwigsbrücke, the putschists confronted and overwhelmed a small group of

policemen. Throngs of shouting, waving supporters greeted the marchers on

Zweibrückenstrasse.

From the Marienplatz, the marchers turned right into Weinstrasse, right again to

Perusastrase, left into Residenzstrasse, and in a few minutes arrived at the

Feldherrnhalle. Here the police had established a line blocking Residenzstrasse,

and there were more police on the Odeonsplatz. A putschist fired a shot, the

police hesitated, then fired back, more shooting occurred, and the putschists

and the crowd of onlookers scattered in all directions. Fourteen putschists and

four policemen died. Hitler was wrenched to the ground, and suffered a

dislocated shoulder. A bullet killed Scheubner-Richter. Göring was shot in the

leg.

From the Marienplatz, the marchers turned right into Weinstrasse, right again to

Perusastrase, left into Residenzstrasse, and in a few minutes arrived at the

Feldherrnhalle. Here the police had established a line blocking Residenzstrasse,

and there were more police on the Odeonsplatz. A putschist fired a shot, the

police hesitated, then fired back, more shooting occurred, and the putschists

and the crowd of onlookers scattered in all directions. Fourteen putschists and

four policemen died. Hitler was wrenched to the ground, and suffered a

dislocated shoulder. A bullet killed Scheubner-Richter. Göring was shot in the

leg.

Ludendorff, who had an iron nerve under fire, emerged unscathed. Oblivious to

the bullets whizzing past his head, he marched straight into the arms of waiting

police and was immediately taken into custody.

When he came to power, Hitler built a Temple of Honor, with iron sarcophagi on

stone pedestals for the “martyrs” of the Putsch. He told Albert Speer

that he wanted his own sarcophagus here. Every November, Hitler and his cronies

re-enacted the abortive 1923 march, pausing to contemplate the inscription at

the Feldherrnhalle honoring the fallen: Und ihr habt doch gesiegt -- And

you were still victorious. (Note the use of the familiar form of address, rather

than the polite Und Sie haben doch gesiegt. Hitler almost never employed

the familiar form in ordinary conversation with his minions.)

When he came to power, Hitler built a Temple of Honor, with iron sarcophagi on

stone pedestals for the “martyrs” of the Putsch. He told Albert Speer

that he wanted his own sarcophagus here. Every November, Hitler and his cronies

re-enacted the abortive 1923 march, pausing to contemplate the inscription at

the Feldherrnhalle honoring the fallen: Und ihr habt doch gesiegt -- And

you were still victorious. (Note the use of the familiar form of address, rather

than the polite Und Sie haben doch gesiegt. Hitler almost never employed

the familiar form in ordinary conversation with his minions.)

The victorious Allies dynamited The Temple of Honor in 1947, destroyed the

sarcophagi, and discarded the putschists’ corpses. But the stone pedestals

remain. Sometimes Nazi veterans gather around them. Historic preservation

officials want to save them as “thought-stones of history.”

![]()

Changing of guard at Temple of Honor, sarcophagi of fallen

putschistists (1938):

Launch Real Player

Launch

Windows Media Player