The first English translation of the

most popular book by the beloved German Jewish children's author, who was

murdered at Auschwitz in 1943.

The first English translation of the

most popular book by the beloved German Jewish children's author, who was

murdered at Auschwitz in 1943.

![]()

Nesthäkchen and the World War

by

Else Ury

Translated from the German, annotated, and introduced by Steven Lehrer

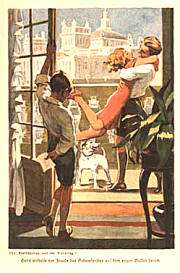

This Nesthäkchen story of a pre-adolescent

girl growing up in Berlin at the outbreak of World War I presents a

charming, skillful evocation of a long-vanished world.

A recent survey of German women revealed that 55%

had read Else Ury's

Nesthäkchen books. Even more had heard them read over the

radio or had seen the

television serialization. These stories show an ordinary

girl growing up, and attempt to explain to children why a girl is so different

from a boy, and so interesting too. At the end of the tenth volume of the

series, the delighted reader comes away with the answer: Girls aren't so

different. Nesthäkchen's adventures had another attraction for children. They

were more factual and showed more of daily life than did other children's

stories of the time. There was plenty of conflict, yet it was good natured and

funny. Even the worst situations had agreeable resolutions.

A recent survey of German women revealed that 55%

had read Else Ury's

Nesthäkchen books. Even more had heard them read over the

radio or had seen the

television serialization. These stories show an ordinary

girl growing up, and attempt to explain to children why a girl is so different

from a boy, and so interesting too. At the end of the tenth volume of the

series, the delighted reader comes away with the answer: Girls aren't so

different. Nesthäkchen's adventures had another attraction for children. They

were more factual and showed more of daily life than did other children's

stories of the time. There was plenty of conflict, yet it was good natured and

funny. Even the worst situations had agreeable resolutions.

But like the popular Wild West books of German author Karl May, the Nesthäkchen

books have not traveled well. Else Ury tried but failed to have her own English

translation published in the late 1930's. (Her English was not very good.) A Dutch translation a few years

earlier was hardly more successful. Yet in Germany, the

Nesthäkchen series is a perennial best seller. As of 1992, seven million copies

were in print. German bookstores invariably reserve a special rack in the

children's department for Ury's Nesthäkchen books.

Else Ury was born in Berlin, November 1, 1877, the third child of third

generation Berlin merchant Jews. Her large, well-to-do, close-knit bourgeois

family provided a loving environment. The experiences of her own happy

childhood, as well as her observation of the growth of her sisters, brothers,

nephews, and nieces, inspired Else Ury to later write her family and youth

books.

Her grandfather, Levin Elias Ury, was director of the Synagogue in the

Heidereutergasse in central Berlin. Her parents, who lived in Charlottenberg,

were no more religious than most of the Christians in the neighborhood. But the

Urys never hid their Jewish origins.

Her grandfather, Levin Elias Ury, was director of the Synagogue in the

Heidereutergasse in central Berlin. Her parents, who lived in Charlottenberg,

were no more religious than most of the Christians in the neighborhood. But the

Urys never hid their Jewish origins.

One older brother, Ludwig, studied law, while another, Hans, studied medicine,

and Else's younger sister Käthe became a teacher. Although women's needs for

education and a profession to secure independence were later a recurring theme

in her books, Else Ury herself pursued no professional studies.

In 1900 Else Ury began publishing travel reports and stories in the Vossiche

Zeitung, a Berlin newspaper, under a pen name. Because a father was supposed to

support his unmarried daughters, if a girl still living at home earned money by

writing, social convention forced her to disguise her identity.

Else's father, Emil Ury, was a tobacco products manufacturer, who produced snuff

and chewing tobacco. When cigarette popularity soared around the turn of the

century, snuff and chewing tobacco sales declined precipitously. Faced with

economic ruin, Emil Ury tried to prevail upon Else to marry the son of a rich

cigarette manufacturer, with the hope that a merger of the two family companies

would follow. But Else resisted this scheme, and remained single her entire

life.

In 1906 Else Ury had her first modest literary success with Educated Girls,

a novel dealing with the very controversial subject of higher education for

women. Indeed, regular women's university studies were first permitted in

Prussia only in 1908. Although Emil Ury's business had gone bankrupt, Else was

able to help support her family with book royalties.

Her breakthrough to bestseller status came with her Nesthäkchen books. Germans

call a spoiled child or family pet a Nesthäkchen. Else Ury's Nesthäkchen is a

Berlin doctor's daughter, Annemarie Braun, a slim, gorgeous, golden blond,

quintessential German girl. The ten book series follows Annemarie from infancy (Nesthäkchen

and Her Dolls) to old age and grandchildren (Nesthäkchen with White Hair).

Despite Else Ury's Jewish background, she makes no references to Judaism in the

Nesthäkchen books.

Nesthäkchen and the World War (1916), the fourth and most popular volume

in the series, sold 300,000 copies. Else Ury wrote the fifth and sixth volumes,

Nesthäkchen's Teenage Years, in 1919, and Nesthäkchen Flies From the

Nest in 1923. She intended to stop there, with Nesthäkchen's marriage, but

her readers simply wouldn't let her. Distraught girls inundated her Berlin

publisher, Meidingers Jugendschriften Verlag, with a flood of letters pleading

for more Nesthäkchen stories. Else Ury obliged her young fans with four more

Nesthäkchen books.

On November 1, 1927, Else Ury's fiftieth birthday, Meidingers Jugendschriften

Verlag gave her a large reception, and announced the publication of an

expensively bound new edition of all ten Nesthäkchen books. The series had been

an immense success, and even the head of the company, Kurt Meidinger, was on

hand to praise Else Ury and her work. The Adlon Hotel, the most elegant in

Berlin, catered the affair, which was attended by many reporters, and chronicled

in German newspapers the next day. In the meantime, Meidingers had established a

special post office box for Nesthäkchen correspondence. Readers sent both

letters and pictures they had drawn for the stories. Else Ury answered all mail

monthly and, from time to time, held parties for her Nesthäkchenkinder, with

cake and chocolate, in the garden of her house. Many of the parties were the

subject of newspaper stories.

Despite

her literary success, Else Ury lived quietly, and didn't consider the details of

her own life to be especially noteworthy. In 1926, with money from her books,

she bought a vacation house in the Riesengebirge area of Krummhübel, which she

named "House Nesthäkchen." Here she and her family spent many summer and winter

vacations.

Despite

her literary success, Else Ury lived quietly, and didn't consider the details of

her own life to be especially noteworthy. In 1926, with money from her books,

she bought a vacation house in the Riesengebirge area of Krummhübel, which she

named "House Nesthäkchen." Here she and her family spent many summer and winter

vacations.

In Else Ury's last book, Youth to the Fore, published in 1933, the author

tried to put a good face on Hitler's rise to power. The book dealt with

overcoming the economic crisis and unemployment, restoring order with a firm

hand, and strengthening Germany. No one is certain whether Ury was politically

naive and had been seduced by Nazi propaganda, or whether her publisher, to

please the regime, had obediently altered the text.

As a Jew, Else Ury was excluded from the Reich Chamber of Writers in 1935, which

meant she was no longer allowed to publish. By 1936, most of her relatives had

emigrated, and her brother Hans had committed suicide. She herself did not want

to leave Germany, because she had to care for her 90 year old mother, Franziska,

who in photographs bears a remarkable resemblance to Sigmund Freud's mother,

Amalie. Else Ury traveled to London, in 1938, for a short visit to her nephew,

Klaus Heymann, but ignored his pleas for her to stay in England. She returned to

Berlin and remained until the Nazis deported her. Her mother died in 1940.

Until 1933, Else Ury lived in Kantstraße 30, then at Kaiserdamm 24. In 1939 she

was forced to move to a "Jew house," a former Jewish old age home in

Solingerstraße 10, where the Gestapo collected Jews for deportation. On January

6, 1943, she had to fill out a declaration of all her possessions, and with one

valise and a few articles of clothing, report for resettlement. She was ordered

to present herself at a collection point, Großer Hamburgerstraße 26, to wait for

transport. On January 11, 1943, she signed a release, turning over all her

property to the German Reich. German officials proceeded to sell off everything

she owned.

On January 12, 1943, the 65-year-old Else Ury was taken to the railroad station

at Berlin Grunewald, along with 1,190 other Berlin Jews, packed into a boxcar,

and deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. A day later, SS doctors selected 127 men

from her transport for labor. SS guards murdered Else Ury and the other Jews in

the gas chamber.

After 1945, Else Ury's books were heavily edited and many contemporaneous or

historical references removed. In 1983, there was a six-part television

serialization of the Nesthäkchen books. Finally, half a century after her death,

her millions of women readers learned the details of her dreadful fate.

A group of high school students from the Robert Blum Gymnasium in

Berlin-Schöneberg discovered the exact date of Else Ury's death on a visit to

Auschwitz in 1995. They also found there her battered valise, labeled with her

name and Berlin address. The valise and other objects and documents relating to

her life were exhibited in Berlin until 2002, when they were returned to the

museum at Auschwitz. They are heartbreaking to see.

Of all the millions of murders the Nazis committed, Else Ury's stands out. Could

anyone imagine the British murdering AA Milne a few years after he had written

Winnie the Pooh?

Nesthäkchen and the World War

Nesthäkchen

and the World War is a difficult book for Germans. After World War II it was

not republished with the other nine Nesthäkchen volumes. The Meidingers

catalogue stated that the book was not a war story or a “hurrah tale.” But it is

by no stretch of the imagination an anti-war book, either.

Nesthäkchen

and the World War is a difficult book for Germans. After World War II it was

not republished with the other nine Nesthäkchen volumes. The Meidingers

catalogue stated that the book was not a war story or a “hurrah tale.” But it is

by no stretch of the imagination an anti-war book, either.

With the country nothing but a heap of rubble in 1945, the Germans wanted no

more to do with the sentiments that had brought them to such a pass. High on the

list were love for the fatherland, exaggerated respect for the military, and

enthusiasm for war.

These sentiments were easy to excise from most of the Nesthäkchen books. For

example, in Nesthäkchen in the Children’s Sanatorium, the volume

preceding Nesthäkchen and the World War, Else Ury describes a German

submarine, which Annemarie watches as it disappears underwater.

"Then it was certainly a submarine, Annemarie," says a companion, "that can dive

and remain submerged for hours without anyone seeing it. We discovered the

submarine to be a weapon for war at sea. God grant that we will never need to

use it." In the revised version

of Nesthäkchen in the Children’s Sanatorium issued in 1950, the submarine

is not mentioned.

But no amount of rewriting could ever remove all objectionable material from

Nesthäkchen and the World War, as it is too integral to the plot. Despite

its enormous prewar success, no German language publisher would touch this

volume.

Else Ury never caught on in the English speaking world, most likely because when

she was at the height of her popularity, either the Germans were our blood

enemy, or the carnage of World War I was too recent for anyone to want to read

about the mind-set of the people who initiated it. Today, though, Else Ury’s

books, particularly Nesthäkchen and the World War, present a charming

evocation of a long-vanished time and place. Germany, a solid democracy, has

been our friend and staunch ally for more than half a century. A modern reader feels deep sympathy for the

trusting, good-hearted, generous people whom a fatuous Kaiser and a pack of

bungling, inept diplomats had thrust into a horrific war. Moreover, Else Ury’s

love for Germany now seems quite poignant and sad, in light of what happened to

her.

The depiction of Nesthäkchen’s abuse of Vera, a Polish-speaking refugee child

whom the author introduces in Chapter 10 of Nesthäkchen and the World War, is

quite upsetting to some German readers. Nesthäkchen mercilessly excludes the

kindly, pathetic Vera from her group and turns her into a school pariah.

In fact, Else Ury has rendered Nesthäkchen as a more believable character

because of her treatment of Vera. Nesthäkchen’s mean streak makes her quite

human. And of course, schoolchildren similarly brutalize each other today,

especially their peers who cannot conform to group pressure, witness the

Columbine High School massacre. Enid Blyton, the English children’s writer with

whom Else Ury is frequently compared, and who is very popular with German girls,

depicts situations analogous to Vera’s.

More important, the device is indispensable for the development of the plot and

leads to the shocking, ringing climax in Chapter 16, one of the most moving

sections of the entire book. Else Ury also skillfully employs exposition and

plot to develop scenes that are laugh-out-loud funny, followed by others that

are highly melodramatic. Nesthäkchen and the World War holds the reader’s

attention from beginning to end. It is not surprising that it was the most

popular volume in the series.

And the book conveys a timeless

lesson, for children as well as adults, about the nature of war. Wars often

begin with a terrific outpouring of patriotic sentiment. World War I started

this way, and Else Ury's description of German war-euphoria in 1914 is chilling.

But Nesthäkchen quickly comes to recognize the hardships and horrors of war, the

dislocations, the pathetic refugees, the scarcity of food, the combat deaths of

favorite teachers, relatives, and friends. In All Quiet on the Western Front,

Erich Maria Remarque describes World War I more horrifically, but he was

writing from the battlefield. Ury's depiction of the war as seen from Berlin,

though gentler, is as powerful as Remarque's. When Nesthäkchen and the World War

ends, in mid 1916, battle had become mass slaughter. Else Ury, unlike Remarque,

simply could not bear the pain of writing about it further.